Friday, December 30, 2011

Pink Eye Lemonade

Pink Eye Lemonade is an obscure little web zine that focuses on weird stuff and that just published my short story "Ptero's Fire." So that's yet another reason to read obscure little web zines that focus on weird stuff. My story is awesome, so are the other Pink Eye Lemonade stories. Drink up!

Reamde

Reamde

Neal Stephenson

Reamde

William Morrow, 2011

1056 pages

3 polychromatic galaxy skulls

Neal Stephenson loves systems. In Reamde, he dotes on systems of land formations, virtual monetary flows, systems of travel—plane pathways and hiker’s trails, organized religious (jihadists), criminal (Russian triad), and guerrilla business (MMORPG extortion) systems, he zooms in for about a hundred pages and details the systems and patterns that go into large-scale urban shoot outs, the physics, for example, of jumping head first into the back of a taxi with a young woman handcuffed to you as the apartment building where you were manufacturing arms for Islamic jihadists is pretty much demolished in sustained gunfire.

Consistently, and kind of brilliantly, Stephenson loves guns. Guns, guns, and more guns pepper this novel like codes in Cryptonomicon. The novel opens with recreational rifle shooting at a family reunion and it closes with recreational shooting at family Thanksgiving. In between, not only are there a number of massive shootouts, but in the midst of non-stop action Stephenson’s characters take the time to reflect on guns. For example, when a Hungarian hacker working for the Russian mafia has a gun at an English jihadist’s temple (in China), the jihadist, a Mr. Jones, waxes textbook on the safety mechanism of the Hungarian’s piece, on the trigger pressure and delay, and on how his own piece is a mite more responsive. Or, similarly, in the middle of the climatic shootout, three characters pause to consider the merits and demerits of a 5-shooter pistol, a sniper rifle, and a shotgun.

If codes and systems of codes provided the central motif of Cryptonomicon, pushing the plot forward with a great deal of intellectual pleasure at the role of intelligence in both big scale military and economic warfare, massaging the ego of the mathematicians who are often left out of such narratives—if codes did all of that in Cryptonomicon, then guns play the same role in Reamde, but it’s more of a spectacle than spectacular. Guns, in this case, are mechanisms of destruction, protection, and, the libertarian strain of the novel suggests, freedom. It is guns that protect Americans from jihadists illegally flying into Canada and hiking across the US border, aimed for Las Vegas. And, of course, it is guns that pose the immediate threat from said terrorists.

Guns are also, the novel suggests, really fucking cool. And that’s about the gist of the novel’s depth. Guns are cool, like blowing shit up is cool, like video games. There’s an odd moment when the protagonist reflects that he and his on-line character are doing pretty much the same thing at pretty much the same time, looking pretty much the same. It’s an odd moment because it celebrates the similarities between the flesh and blood reality of a man with a gun pointed at him and his family, and an online avatar that, uh, that’s just that.

Saturday, December 24, 2011

Spellfire, Self-Help, Dictee

Question: What do Ed Greenwood’s fantasy Spellfire, Lorrie Moore’s first collection of short stories, Self-Help, and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s DICTEE have in common? Answer: not much other than I read them recently. Furthermore, they were published in the 1980s (respectively 1988, 1985, and 1982). They are all works of imaginative writing; and finally, each of these works has a slightly seminal status in US fiction.

Spellfire (1988) was the first novel by Ed Greenwood set in the Forgotten Realms, a world he created. A number of characters, myths, regions, and plotlines that have reappeared for the past 20 years were first introduced therein. Spellfire is often overshadowed by the commercially more successful Icewind Dale trilogy, the first book of which was published the same year (1988). Elminster, the society of Harpers, the Dalelands, and Zhentarim are all introduced here for the first time in the form of a novel. Perhaps most importantly, though, it is the first demonstration of Ed Greenwood’s great sense of humanity and humor and his ability to render this sensibility through witty dialogue.

Spellfire (1988) was the first novel by Ed Greenwood set in the Forgotten Realms, a world he created. A number of characters, myths, regions, and plotlines that have reappeared for the past 20 years were first introduced therein. Spellfire is often overshadowed by the commercially more successful Icewind Dale trilogy, the first book of which was published the same year (1988). Elminster, the society of Harpers, the Dalelands, and Zhentarim are all introduced here for the first time in the form of a novel. Perhaps most importantly, though, it is the first demonstration of Ed Greenwood’s great sense of humanity and humor and his ability to render this sensibility through witty dialogue. Self-Help (1985) was ground-breaking when it first appeared on shelves, contributing to the renaissance of the US short-story, the ensuing proliferation of MFAs and journals devoted to creative writing, and a “feminine” aesthetic that is shared by such otherwise disparate personalities as Martha Stewart, Miranda July, and Liv Tyler. In other words, she provided an aesthetic and intellectual dimension to an emerging self-help culture targeting women: bubble butts, bad affairs, tension with mothers and children, jobs of drudgery, repetition and, ultimately, always, language. Moore put language at the heart of everything else, from pathos to bathos, and by so doing provided an exciting new approach to the meaninglessness and passions of existence. This approach is echoed in the title of her collection and the introduction of the “How to” genre as imaginative prose—the absurdity and inexplicably suddenly very necessity of the prescription.

DICTEE (1982) is a highly experimental, multi-genre work. Miranda July comes to mind for comparison, but only because both artists work in film, performance, and writing. The work moves through generic linguistic registers (autobiography, biography, eschatology, poetry, text book, history, memoir, lists or notes, philosophy), languages (French, Korean, Chinese, English), and intersperses a strong visual element, including charts, maps, diagrams, heavy enjambment (like entire pages are “enjambed”), photos, drawings, and hand written text (in various languages). Unlike Spellfire and Self-Help, DICTEE cannot readily be tied into a commercial industry or an economy of cultural desire. Using a chemistry metaphor, it breaks down literary elements as it breaks down nationality, ethnicity, and language.

DICTEE (1982) is a highly experimental, multi-genre work. Miranda July comes to mind for comparison, but only because both artists work in film, performance, and writing. The work moves through generic linguistic registers (autobiography, biography, eschatology, poetry, text book, history, memoir, lists or notes, philosophy), languages (French, Korean, Chinese, English), and intersperses a strong visual element, including charts, maps, diagrams, heavy enjambment (like entire pages are “enjambed”), photos, drawings, and hand written text (in various languages). Unlike Spellfire and Self-Help, DICTEE cannot readily be tied into a commercial industry or an economy of cultural desire. Using a chemistry metaphor, it breaks down literary elements as it breaks down nationality, ethnicity, and language. Ultimately it always comes back to language. The protagonist of Spellfire is a young woman named Shandril who at the opening of the novel longs for adventure. By the end of the novel she is battling an ancient undead dragon. Adventure indeed! This kind of male (oriented) fantasy is the sort of indulgence that the narrators in the stories of Self-Help resist while at the same time long for. They speak from the tension between resistance to and longing for an order that will readily consume them. DICTEE grapples with the historical and epistemological conditions of just such an order, but at the level of “ideology,” of nationality, ethnicity, of political territories that grand institutions of power kill for, that young women die as martyrs for, and always at the level of language, always as a performance. In this sense, the undead dragon (technically called a dracolich) is a fantastic projection of history itself (playing here on David Der-wei Wang’s discussion of “the monster that is history,” in the book by that name) and the death drive that lends DICTEE its pathos, to end historical tensions as a martyr, as a symbol or sign and thereby confirm a repressive symbolic order that one longs for and resists, is redirected in Spellfire as the pleasure principle, as wish fulfillment, that dreamwork. Shandril, that unlikely hero, absorbs all power and unleashes it at will. In the hands of such an innocent, the dracolich of history must face itself and be destroyed, the inverse of Nietzsche’s over-cited maxims: stare at the naïve barmaid and the pretty barmaid stares back (or, that which does not kill us makes us a naïve barmaid).

Monday, December 19, 2011

Titus Andronicus

For me, the most memorable line from Titus Andronicus is the one that sets the horrific events in motion, hissed by Tamora, Queen of the Goths, in Act I:

I'll find a day to massacre them all

And raze their faction and their family,

The cruel father and his traitorous sons,

To whom I sued for my dear son's life,

And make them know what 'tis to let a queen

Kneel in the streets and beg for grace in vain.

The Public Theater’s current production of Titus Andronicus takes an almost playful spin on the massacre that follows. More than anything else, it seemed like the sort of visual spin Tim Burton would have put on the gory play—gothic, visually riveting and disgusting, a bit campy, and overall playful. So, by the time Tamora tries her meatpie (with her own sons cooked in), most of the audience was ready to laugh (cathartically, one hopes). Which isn't to say that there aren't many moments of collective gasps.

I'll find a day to massacre them all

And raze their faction and their family,

The cruel father and his traitorous sons,

To whom I sued for my dear son's life,

And make them know what 'tis to let a queen

Kneel in the streets and beg for grace in vain.

|

| Picture from the NYT review, here. |

Saturday, December 3, 2011

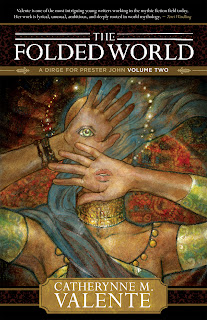

Catherynne M. Valente: A Dirge for Prester John, Vols. 1 and 2

4.5 Polychromatic Galaxy Skulls

4.5 Polychromatic Galaxy Skulls

A Dirge for Prester John centers on a late 17th century expedition to find Prester John, a Nestorian priest who journeyed east from Europe some seven centuries earlier and who is presumably still alive since he drank from the fountain of eternal life. The major strand of the novel, and the series as a whole, is the journey of Prester John himself (vol. 1), his rule in Pentexore (vol. 2), and, one may presume, his kingdom’s decline (vol. 3).

A Dirge is literary, fantasy, historical, mythological, folkloric, lyrical, poetic, and experimental, at once. It’s also philosophical, theological, and gorgeous. They both participate in and rejuvenate a literary tradition of journeys and first encounters that one can trace back to Homer’s Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, to name a few. Along with the journey/quest motif, A Dirge shares at least one thing in particular with each of these works: an encounter with the bizarre/surreal/weird (call it what you will)—half-swan humanoids, genderless angels, headless women with eyes for nipples, butterfly nannies, talking animals, a fountain of eternal life, book trees, bed trees, trees of anything one can bury.

A Dirge is literary, fantasy, historical, mythological, folkloric, lyrical, poetic, and experimental, at once. It’s also philosophical, theological, and gorgeous. They both participate in and rejuvenate a literary tradition of journeys and first encounters that one can trace back to Homer’s Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, to name a few. Along with the journey/quest motif, A Dirge shares at least one thing in particular with each of these works: an encounter with the bizarre/surreal/weird (call it what you will)—half-swan humanoids, genderless angels, headless women with eyes for nipples, butterfly nannies, talking animals, a fountain of eternal life, book trees, bed trees, trees of anything one can bury. Two Warnings:

Warning the First: Catherynne M. Valente knows more than you. This is writing that challenges readers (or this reader at least) to expand with it or be lost. It’s neither easily consumed nor pandering to consumers. It’s aggressive, gorgeous, and unapologetic prose. In this novel, Valente uses Greek myths (the scenes with Leda’s offspring are some of my favorite), medieval lore (Prester John himself is a legendary figure from the Middle Ages), and Judeo-Christian myths to build an utterly unique and thriving world within a world. For every myth I recognized (Thomas the Doubter, for example, but only the slimmest thread) I’m sure that there were many that I didn’t. And I don’t know that it matters.

Warning the Second: Catherynne M. Valente is more imaginative than you. Be prepared to expand your powers of visualization. The incredible scenes she composes are rendered in such a way as to leave me both ecstatic and exhausted every five pages or so. Not keeping up with Valente’s images means losing the thread of the story, which means wandering for pages in way over your head. Since I’ve mentioned the Leda myth, I'll use it as an example. Here’s how the myth is told to one of the main characters, with my thoughts interspersed in brackets:

But my friend who piles up olive pits among the columns [can you visualize that?] whispers [hear the voice] to me through the mountain-roots [okay—what? mountain- roots? literally?] that Leda had a fifth child, who did not have the beauty to fill out recruiters’ rolls [what rolls? recruitment for what?], but the head of a swan and the body of woman, a poor, lost thing, alone in her egg, without another heartbeat to keep the beast in her at bay [does that mean anything more than that she’s alone? is she really in an egg, or is that a metaphor? in this context, is the woman side of her the beast or the swan?].

And it goes on like that, with an especially surreal image, a repeated motif throughout the novel, of a “dry sea that hurls its sandy waves at [the swans’] nests on the golden cliffs” (36).

No piece by Valente is for the faint of heart, certainly not this series. It requires a commitment, and the experience may very well transform you. She writes challenging works—intellectually demanding and artistically brazen—that become spiritual experiences.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)